How I Overcame Regret and Learned Self-Compassion

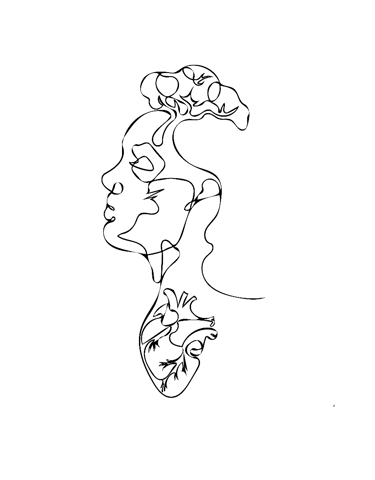

If regret had been one of the greatest struggles in my self-reflection journey, learning to forgive and be more compassionate with myself has been its antidote. Regret used to push me down a downward spiral, leading to self-hate and constant self-criticism, that I could hardly brake until I forgave myself.

Yet, compassion did not come easy for me. I had a natural disposition towards regret, as I never thought highly of myself and was a perfectionist in everything I did. I would penalize myself for every mistake I made, often punishing myself for not progressing faster. Countless times during my reflection efforts, I had thoughts such as: Why didn’t I learn this earlier? Why did I not just act differently? Why didn't I start working on myself earlier? The biggest challenge for me in overcoming regret had been its backward-looking nature. I never gave up on the idea that Jana was meant for me, clinging to the past and wishing to undo it, thus fueling my regret. Forgiveness, on the other hand, was forward-looking. It didn't require me to deny my mistakes but shifted my attention to the future and strengthened my belief in myself going forward.

Challengingly, given my tendency for self-criticism, I had to learn to forgive myself from scratch. While reading various self-love books, I came across some major concepts that helped me change the perspective I held towards my past actions. Although I didn't immediately change my mindset after reading them, I constantly reminded myself of these ideas whenever regret surfaced, and over time, I became better at showing myself compassion.

The first idea that helped me was to start seeing my process as a collection of small and medium-sized steps. I came across the idea while reading Mark Manson's book “Models”. He argues that when one focusses on too many things at once, it becomes harder to make progress and even worse, one becomes prone to overlook what one has achieved so far. This certainly was true for me; until this mindset shift, I was solely focused on achieving my end goal of happiness and confidence and therefore tried to change my whole being at once. As a result, I often grew tired of not progressing quicker. I criticized myself for not feeling significantly better even after all the work I had done. It was especially hard when my progress inevitably slowed down for a couple of days or weeks at a time. When this happened, it was difficult for me to value the steps I had already taken. I had managed to overcome my fear of approaching women, I was questioning some of my beliefs regarding my attractiveness, I had already learned a lot about myself, I'd opened up to friends, and I could force myself to act confident more frequently. Consciously reminding myself of these improvements helped me a lot in stopping my dysfunctional self-talk, motivating me to push forward, and ultimately increasing my mood.

Building on the idea of seeing my journey as a series of individual steps, I realized it was crucial not to become overly obsessed with self-improvement. In the beginning, I was guilty of wanting everything too quickly – I wanted to transform my life as fast as possible, understand myself, change habits, and override self-limiting beliefs. Every waking hour was spent either learning or working on myself. Even when I was out with friends, self-improvement was always on my mind, and I couldn’t wait to share my latest insights. It became the dominant topic of many conversations. I didn’t recognize the downsides of this mindset until I read about the Tao principle in The Untethered Soul. The core idea is simple: extremes are unhealthy, and balance is key to a happy, calm life. The author illustrates this with an example of a heavy smoker who quits. A year later, when asked how his year has been, he only talks about quitting – what he tried, the struggles, the victories. Quitting smoking became his entire identity. That struck a chord. If I continued down this path, I’d burn out. I had already noticed how draining it was, and when I felt mentally exhausted, I became more vulnerable to regret and self-criticism. I had to make my journey sustainable by allowing myself breaks—reading something unrelated to psychology, spending time with friends without discussing my struggles, or even just watching a silly sitcom. I had to remind myself that rest wasn’t a setback; it was necessary to keep going.

The Tao principle also helped me in a second aspect, as it caused me to be less harsh on myself by seeing reasons for some of my actions. In line with the idea of keeping balance, the author introduces the metaphor of a pendulum, stating that if the pendulum is kept at the extreme for long, it will swing even harder to the opposite side thereafter. He even uses relationships as an example to make his point. Extreme forms of affection with contact either every waking minute or barely any contact at all are equally bound to fail. Yet, if someone had been lacking love for a long time, he or she may be more prone to look for the other extreme. It was spot on in regard to my situation before I met Jana and reading through it did help me a lot. I was beating myself up for pressuring her so much and not giving her more space. However, the mere fact that I wanted a relationship for a long time obviously increased the importance of the relationship for me, as well as the anxiety of losing it. This wasn't a new realization, yet I had cast the argument aside because I didn't want it to function as an easy excuse. Now my outlook on it has shifted. It did not take away any of the responsibility I had, nor did it neglect the importance of addressing the self-doubts that were feeding the low dating success to begin with. Nonetheless, instead of beating myself up over it, I now saw it as a way to understand myself better.

Personally, I found the most powerful concept to be the idea of always being one's own best friend as postulated in "12 Rules for Life" by Jordan Peterson. From a content perspective, it perfectly summarizes all of the aforementioned ideas, but it additionally gave me a practical solution how to provide myself with such compassion. Every time I noticed negativity creeping up on me or when I ran into a problem I hadn't yet fully analyzed, I would ask myself, "If my best friend came to me with this problem, how would I treat him?" This question allowed me to easily apply the learnings from the previously mentioned principles and notice when I wasn't applying them. I would remind my best friend of the steps he had already taken and tell him how proud I am of him for doing so. I would tell him he isn't a failure just because he isn't there yet. I would show compassion with him and find reasons for his actions instead of putting all the blame on him. Yet, I wouldn't lie to him and held him accountable to work on himself and improve what he wants to improve going forward. However, I would do so in a trusting and motivating manner, cheering him up instead of putting him down. I would support him in his grief as well as his journey and would make sure he knows I am there should he fall. All of this I would do for a best friend, though I had been seldomly doing it for myself. It may sound obvious, but it was something I certainly needed a reminder of. It took time to get the hang of it, but by continuously asking myself how I would treat my best friend, forgiving myself became way easier.

The last idea that helped me was to realize that I always did my best. The thought of "I should have been better" had been dragging me down for a long time. I could list many mistakes and situations where I wished I had acted differently. I even knew to some extent in the moment that I would push Jana away. So, how could that potentially have been my best? My perspective changed after listening to a podcast by a man named Matthew Hussey. In it, he argued that doing your best does not equal applying the best possible behavior, but instead means doing the best you could have done at that time, given your experience, emotions, skills, and knowledge. He further explained that even if you thought you knew something was wrong, you might have known it rationally, but not emotionally. For him, desiring a different behavior is like wishing for another reality. That version of you would have always done exactly what it did. He certainly has a point there.

If I could go back, I would still have acted the same way. It was only through the outcome and subsequent learnings that I became able to imagine a different behavior. There was no scenario in which I could have acted differently in that moment. Accepting this wasn’t easy nor did it make my sadness disappear, but it made me confident to do better next time, stopped me from beating myself up and helped me in focusing more into the future instead of the past. I did what I could at that time, and I was about to learn from it.